Gladiator Gasperini’s New Life At Roma

After a decade in Bergamo, Gasperini joined Roma at an interesting point in his career. Two decades of coaching, still relevant. Over nine hundred Serie A points, still wanting more. They have started in excellent form, but will his tactical framework provide the Scudetto that both club and coach have longed for?

Written by Joel Parker.

We decided to make this article free to read. If you want to support our work, consider taking a subscription.

In the midst of Serie A’s coaching carousel, Roma pulled the best card to entice Gian Piero Gasperini down to the capital.

It’s not like The Friedkin Group has been entirely fixated on one tactical vision. One of Roma’s finest generals, Daniele De Rossi, had the ideas but not the coherence. Issues were aggravated when Ivan Jurić, seen as a Gasperini disciple in Italy, failed to spark new life mid-season. However, a resurgence under Claudio Ranieri saw the Romans rise up the table, narrowly missing out on the Champions League spots with just one Serie A defeat in the new year.

As Roma churned through coaches, Gian Piero Gasperini had his deepest set of attackers in his final year at Atalanta Bergamo. After a slow start, eleven straight wins (including a 3-0 victory at the Maradona, against the eventual champions) had his team in the Scudetto talk come Christmas. Despite Atalanta fizzling out of the picture, nothing could take away the miracle of the Goddess. Gasperini had achieved reclamation, a coach deemed incapable of taking the big jobs, so he made a big club out of his own ideals, which peaked on an incredible night in Dublin.

A coach with a strict blueprint, Gasperini’s journey to the elite in the Italian game has not been linear. At Genoa, he turned them from Serie B to the Europa League, their highest position in nineteen years. Eighty-nine days at Internazionale soon clouded over this achievement, before he was sacked at Palermo (in fairness, who wasn’t), returned to Genoa, and only bought himself more time at the start of his career in Bergamo when he sent the kids out to play Crotone. Gasperini has been rooted in Serie A, but his story totes a Clough-esque redemption.

His move to Rome comes at an interesting juncture in his career. The sixty-seven-year-old departed Atalanta after nine years to a project that had been bubbling with both high expectations and toxicity. However, Roma have started in excellent form: eight wins in the first eleven games and conceding the least amount of goals in Europe’s big five leagues. Like last season, the legitimacy of a Gasperini team’s capability to mount a title charge comes into question. So, are Roma in a position to join a tight title race?

The same intentions

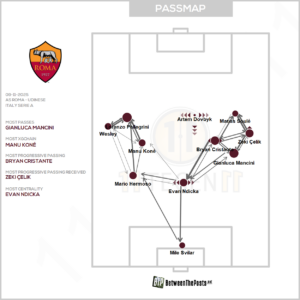

Regardless of the coach, the Roma squad has been accustomed to playing in a variation of 3-4-2-1 or 3-5-2 formations for quite some time, especially in its defense. Within this model, Gianluca Mancini and Evan Ndicka had been the center-backs moving into higher positions within the build, for rotations to be connected. Under Gasperini, Ndicka has seen more time as the central center-back.

Setting up in the same formation, Roma have been prepared to play the traditional Gasperini beats. In possession, this is particularly influenced by the center-midfielders dropping into deep and wide areas of the field; ex-Atalanta player Bryan Cristante is already well-versed in this adjustment. However, the profile of player varies in comparison to one that the coach traditionally likes. None more obvious than the options at wing-back, where Wesley, Zeki Çelik and Angeliño don’t have the same levels of physicality as those who had usually occupied these spaces in the past. Whereas Joakim Mæhle, Hans Hateboer or Robin Gosens used to box crash for goal threat, the wing-backs of Roma specialize more in the rotations to gain territory, although Wesley has the offensive potential.

Passmap from Roma’s most recent game against Udinese, with some classic Gasperini tropes. Ultra wide 3-4-2-1 formation, with few connections between the center-midfielders and triangles in the channels.

In the attack, Roma has excellent technical capabilities in Paulo Dybala and Matías Soulé, although the pieces around them are a little more awkward. Evan Ferguson had this potential as a striker who could link, but fitness issues have seen his minutes drop. Artem Dovbyk seemed out of favor with Gasperini, whilst the attack misses a player who could dominate in the halfspace on the left side. As a result, Roma have leaned towards playing with Dybala, Soulé and Lorenzo Pellegrini in an offensive structure which harks back to Ademola Lookman and Charles De Ketelaere splitting wide for Mario Pašalić to be the central presence (for Roma, this would be Dybala). With the intentions being the same, pros and cons have arisen once more.

All channels, no center

Having midfielders drop into your first line is not unfamiliar to Serie A, but having two continuously bounce between the center and fullback spaces creates an unusual dynamic. On the plus side, Roma is a hard team to press once they enter this buildup phase. Therefore, the opposition chooses to shield the pivot space or passively man-mark without much engagement. In a league limited in high pressure, Roma does not have to produce patterns from short goal kicks to get the ball towards the halfway line.

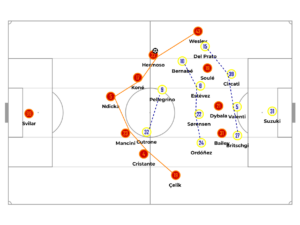

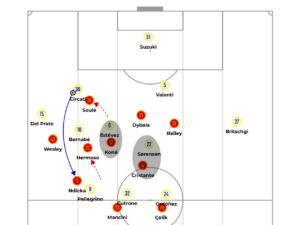

It is in these scenarios, against a passive medium block, where some issues start to appear. Cristante and Manu Koné’s deep engagement means that Roma can end up with too many players behind the ball or sitting out wide without movements from inside the block.

11th minute, versus Parma (2-1 win): As Mario Hermoso carried, both center-midfielders were positioned in a wide split behind the ball. Çelik and Wesley held width, but Roma was positioned with seven players on the outside of Parma’s 4-4-2 zonal medium block. In this sequence, Hermoso would try to underlap Wesley, the pass went back to Koné, and his attempted line-splitting pass towards Dybala’s curved run would be intercepted by Alessandro Circati.

Filtering out the center of the pitch leaves Paulo Dybala, or one of the strikers, with very limited options when Roma tries to interplay inside the block. Soulé can be active in the pockets, but the Argentine winger is more comfortable when he has room to take touches down the channels. Combinations can flourish from this dynamic, but the box presence is nonexistent when both Dybala and Soulé are also encouraged to move into positions outside the block. Even when Gasperini picks a 3-5-2 formation (Neil El Aynaoui as a third center midfielder), Roma are easily encouraged into their U-shape and without the interior options, they can be easy to defend against.

16th minute, versus Inter (1-0 loss): The ultra-wide buildup may have given Roma security when circulating around Inter’s 5-3-2 defensive block, but the lack of players inside the block meant that Inter could step out easily. A one-two was attempted down the right side, but an overhit pass saw Acerbi recover the ball as the away side maintained their defensive overload.

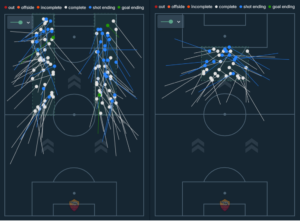

Using data provided by MyGamePlan, we can see that Roma exerts a lot of possession control (3rd best in Serie A) without much penetration. Gasperini’s team ranks 5th for progressive passes (72.19 per 90), but it’s where these passes aren’t being headed that showcases their problems. Roma ranks 9th for progressive passes that end up in the attacking halfspaces (8.16 per 90). In zone 14, which is located directly in front of the opponent’s penalty area, they rank 8th (3 per 90) amongst the rest of the teams in Serie A. They may have plenty of the ball, but Roma are producing mid-table numbers despite their technical capabilities.

Left = Number of progressive passes by any player of Roma, ending in left or right attacking halfspaces (that are short or medium length). Right = Number of progressive passes by any player of Roma, ending in zone 14 (that are short or medium length).

Why Roma is producing these numbers is not just down to the structure. Much of their buildup for the past two seasons had relied on Leandro Paredes dropping into the defensive line and utilizing his passing range. Without a direct replacement at the base, Roma is more limited with the Cristante and Koné duo, even if both are more capable of actively joining short rotations. The other question is whether Gasperini’s tactical blueprint can get the ball into the center of the field, or in optimal situations for the attack. If we look at the same metrics from last season, Gasperini’s Atalanta ranked 7th for progressive passes into the halfspace (8.67 per 90, Roma 3rd on 9.97) and 2nd for zone 14 (4.2 per 90, Roma 4th on 3.47).

It is an unusual turn of events from a coach whose claim to fame had been the halfspace work that saw Atalanta score goals, effortlessly. The combinations that Atalanta produced came through Ademola Lookman’s elite work and dynamism in the pockets, alongside Éderson, who he could bounce off. Soulé has the potential on the opposite flank to gain entry into these areas, although he will need more assistance from Roma’s current combinations. Koné and Cristante are the top two players making these progressive passes into the halfspace/zone 14. Cristante’s physicality does offer a box presence, but not the fluid short sequences which Soulé could benefit from.

Potential dynamics are present

However, the wide stances that Soulé takes up have produced a threat. Against back fives, Soulé’s take-on ability constantly sees him fouled and attracts the left-sided center-back to follow him into wide areas. Through Mancini moving up the lines and Wesley/Çelik also joining the attack, Roma are quite consistent in pulling space open down the outer right channel. Mancini and Çelik (recently, Wesley has played left wing-back to cover for Angeliño) have been able to show some fluid exchanges. Against Udinese, their movements influenced both the penalty that was awarded for Roma, and they produced a one-two inside the box for Çelik to score the second.

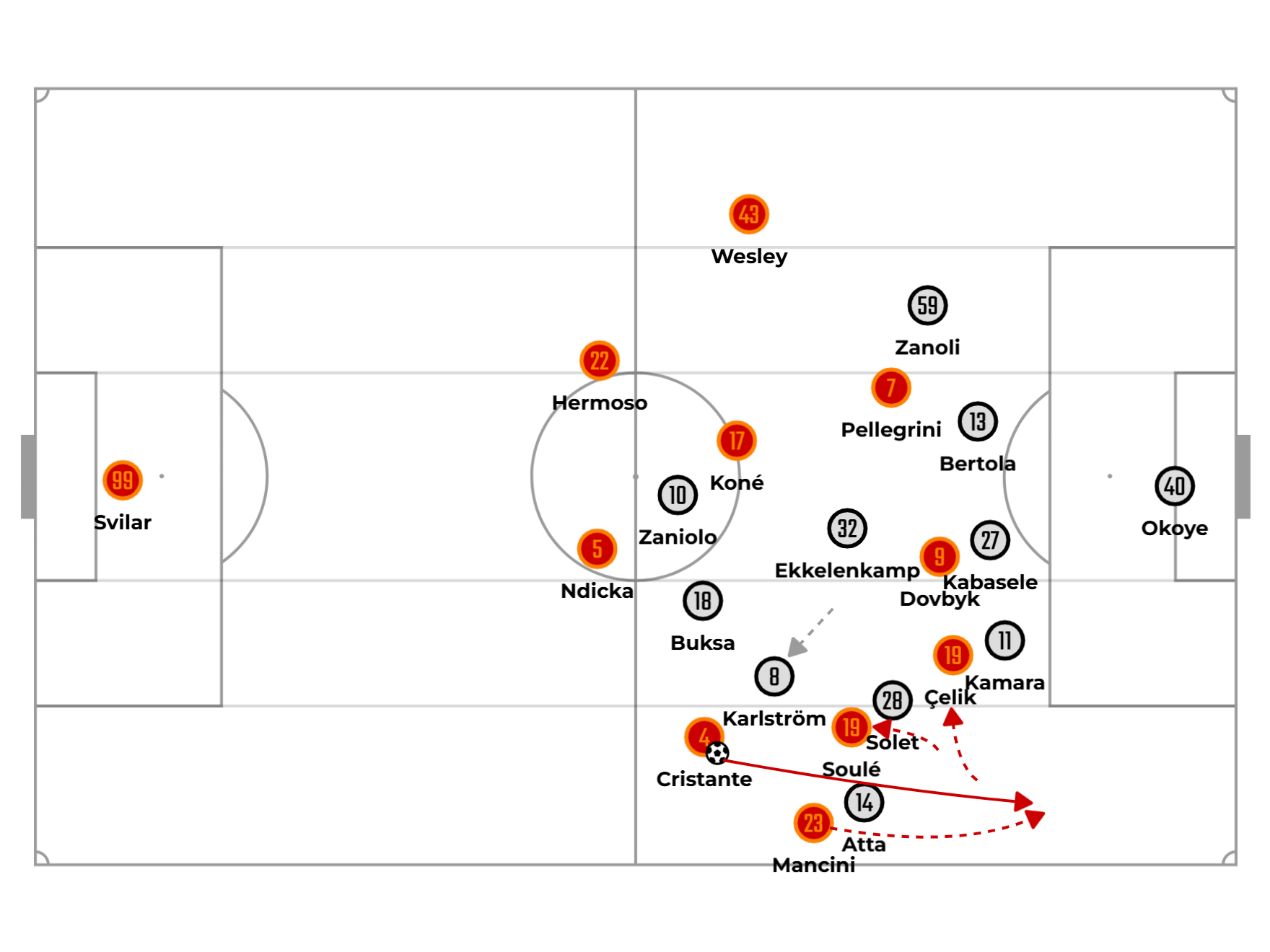

36th minute, versus Udinese (2-0 win): Soulé encouraged Oumar Solet out of the defensive line, which gave room for Çelik to take Hassane Kamara inside the block. As a result, Cristante could chip the ball over the left side of the defense, as Mancini moved around Arthur Atta, and crossed towards Çelik, which struck the hand of Kamara.

When Soulé drops out of the block and towards the touchline, it’s these runs from Mancini and Çelik that can offer more direct threat for Roma. Both players can also underlap as the Argentine looks to take players on or stretch the defense vertically to create more isolation. When the wing-backs drift from out-to-in, against the defensive line, this encourages more diverse movements from deep, as Roma can stop the opposition center-back/wing-back from jumping up the chain to support the midfield; therefore, more space opens for a direct ball or even one-twos.

14th minute, versus AC Milan (1-0 loss): El Aynaoui’s run was not connected, but Wesley passed back to Cristante. By drifting inside, Saelemaekers could no longer jump, and the Milan defensive line was too deep as Fofana tried to engage with Cristante. As Fofana was isolated in his jump, the one-two could be made between Dybala and Cristante. In this phase, Cristante would dink the ball through to Wesley, who ran on De Winter’s blind side, but his shot was gathered by Maignan.

However, the attack appears to be much more refined (or at least has a higher ceiling) on the right side than on its left. From the first line, Gasperini has struck a better balance with Hermoso on the left, Mancini on the right and Ndicka at the center of the back three. Hermoso does not carry or aggressively run as much as Mancini, but he can influence through his passing. Koné has offered a lot from the middle third through his ball carrying, whilst Wesley has produced some dangerous phases when he can run back inside with the ball on his right foot.

Though there are neat profiles on the left side, Roma has struggled without an imaginative influence on that side of its attack. Dybala has briefly featured in this role, whilst it looked like Lorenzo Pellegrini could make the position his own after scoring the only goal against Lazio. Performances have fizzled since then, and Roma could do with an extra player who could actively disrupt defensive blocks from the inside, or at least the halfspace. With these dynamics at play, Roma’s attack shows promise but has been very inconsistent. When Roma wants to get the ball into the box, it must rely on Dybala (20 passes in total) and Soulé (17 passes, making the Argentines the top two performers in the team by this metric), moving out of the forward line so they can be activated. The box presence is rarely replicated: Roma ranks 16th for successful cutback crosses in Serie A (0.42 per 90). Plenty to work on.

Vintage off-ball operations

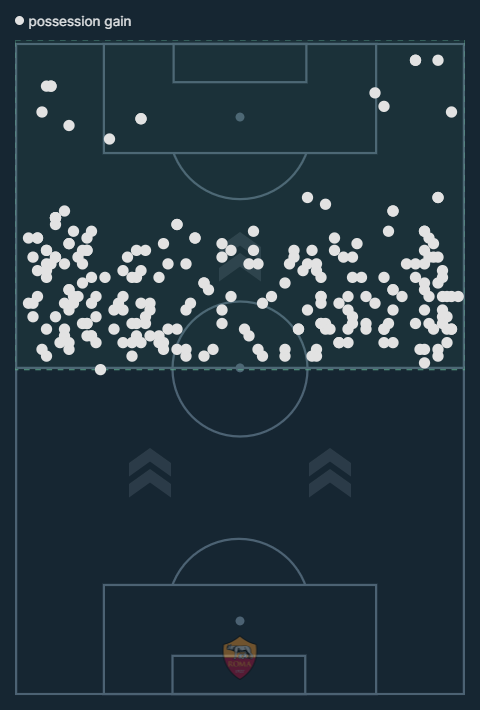

It is no surprise that Roma were going to defend in Gasperini’s trademark man-to-man scheme, but its application has been their biggest strength so far. The scheme in question has lowered in intensity over the years: man-marking has been ever-present, but occupation of another player has grown in distance to provide better support for the center-backs. As a result, Roma is not making the regains in the final third, but it is producing turnovers once they have cornered their opponent and forced them to go more direct. The stats back this up: no team has made more possession regains in the attacking half (20.4 per 90, the closest is Inter on 17.88) and the success rate of the opponents’ passes in their first third (69.33%) is only topped by Napoli (69.14%).

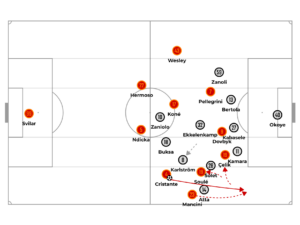

Scatter plot of all Roma’s possession regains in the attacking half. The vast majority around the middle third area.

As a result of minimal deep buildup work in Serie A, plenty of these regains would come from long ball exchanges and knockdowns being mopped up. However, in these situations, Roma has been very quick in resetting its defensive arrangement. Soulé and Dybala have been strong in pressing outward, but it’s the reading of these situations, from the first line of pressure, that has kept the pressing structure. For example, Bologna is a team which likes to utilize its goalkeeper, with more adventurous center-back rotations (a team which has caused Gasperini problems in the past). As Pobega dropped between the striker split, Bologna had an exit with a two-versus-one on Ferguson. However, the Irishman would laterally cover both the pivot and Casale, at center-back, to jump towards the recipient. It is in these phases that Roma excels in putting the pressure on the opposition down the channel, and forcing the long-ball for the likes of Ndicka to clear up.

Whilst Gasperini’s reshuffle in the center-backs had in-possession benefits, it also strengthened their resolve further off the ball, as Hermoso and Mancini are more than comfortable in jumping out of the defensive line. It’s this commitment that keeps the structure intact when Cristante/Koné are occupied by opposition players in deeper positions of their buildup.

9th minute, versus Parma (2-1 win): Roma’s aggressive man-marking forces the turnover. Soulé encouraged Circati to play a long pass down the channel by pressing outwards, whilst both Wesley and Hermoso were in a position to press on Adrián Bernabé for the short pass. Circati opted to go long, and as the Roma defense had shifted, Ndicka was in a position to win the aerial duel, which led to a pass that ran through to Dybala.

Despite their achievements, some curious decisions from Gasperini have led to some awkward moments. Against Inter, they were able to encourage Koné to follow Hakan Çalhanoğlu into more central areas, which saw the distance grow between Hermoso and Nicolò Barella in a deep-right position. Mancini and Ndicka had swapped positions, and an unusual trigger of an offside trap saw Ange-Yoan Bonny stride past the last line with ease.

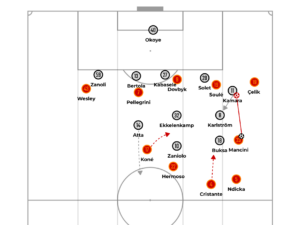

Against AC Milan, Koné was left deep in the rest defense, tasked with stopping Rafael Leão on the transition. However, his management in these situations left Roma compromised, as Leão was still given plenty of room to maneuver, as seen in Strahinja Pavlović’s goal, where Milan broke through. In fact, their overperformance in Expected Goals can be attributed to this game. Out of the 3.81 xG from Milan, 2.7 xG was produced in open play. This would be inflated by some poor giveaways from Roma in possession, which saw Roma being exploited without being punished.

38th minute, versus AC Milan (1-0 loss): Buildup to Milan’s goal. A delayed counterpress on Ricci saw the passing lane open to Saelemaekers. In the rest defense, Gasperini had instructed Koné to stay deep, to occupy Leão, but the Portuguese winger was left free to stretch the center-backs.

A counterpress with conviction?

Despite the strength of their man-marking scheme, defending transitions has proven to be a more difficult task. With Cristante and Koné dropping so deep in possession, Roma may be a difficult team to press, but the opposition can engineer sequences when Roma gives the ball away. Both center-midfielders are encouraged to push up the chain to engage, often against midfield threes with opposition forwards still deep to bounce off from. Once again, this is reflected in the data. Roma rank 10th for opposition transitions that lead into shots (5.08%, 38 shots from 748 possession gains). Meanwhile, Roma rank 12th for possession gains, made by an opponent, which leads to a completed final third pass within 20 seconds (3.58 per 90), the worst out of the teams in the current top seven.

The bulk of these turnovers are when Roma tries to play through the lines and neither of the center-midfielders is in a strong counterpressing position. This is when an opponent’s directness can be a much more dangerous proposition, especially when Mancini or Hermoso is already committed to the attack. With both wing-backs being width providers, their positions are often way ahead of the ball, so Roma can find itself quite vulnerable on the far side.

25th minute, versus Udinese: Buildup to Atta’s chance. After Mancini’s pass was intercepted, both Koné and Cristante applied pressure in an area where they were underloaded against the Udinese block. As Zaniolo occupied Hermoso, Atta made a run behind the defensive line and was connected by Karlström’s long ball over the left side of Roma’s defense.

Three of the five goals that Roma have conceded so far this season have all come in similar situations. An attack breaks down on the right side of the Roma attack, and the opponent has a direct exit in the outer channel. The defeat to Torino should have been a warning sign for the game against Milan: Kristjan Asllani was able to clear to Nikola Vlašić, who received behind Tommaso Baldanzi, and Welsey was late to jump on Vlašić. In the process, Giovanni Simeone skinned Koné, and although Roma’s defensive line made a recovery, Simeone still scored through a fantastic shot. Moise Kean also required an excellent shot from outside the box to score, but his goal came through a messier sequence as Mancini originally won the duel, only to dribble into problems, and Hans Nicolussi Caviglia played the pass over the top for Kean on the one-versus-one.

Roma is a team that actively tries to counterpress. Although their management of long balls aimed at the opposition striker has been good, the distances that their midfield must cover can be too large, depending on the situation. Fortunately, this is a league that is played at a lower speed and with much less transitional threat. Even with a counterpress that is less refined than its out-of-possession arrangement, Roma can get away with more domestically. How this would look against some teams in the Europa League begs a different question.

Takeaways

The Friedkins have never been too shy about making statements: whether it’s Paulo Dybala on the steps of Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana or their attempts to Joséify the club. Hiring Gasperini is well within this playbook: a coach who is still very relevant and has brought success to Serie A’s best-run club over the last decade. His framework has been tried and tested: Roma has replicated this efficiently out-of-possession, but on the ball, questions still linger as they encounter plenty of issues upon the halfway line.

There is a reason that Roma has scored few goals so far this campaign, but Gasperini is a coach who can ignite the creative profiles through the terms of his arrangement. Whether an injury-prone Dybala or the young Soulé can carry this burden towards a Scudetto is unlikely, but their strengths off the ball, as a unit, see them as worthy contenders for the top four spots once again.

Comments