The top five tactical switches at EURO 2020

In knockout football, having a manager that can successfully change the tactical approach is a superpower. Even more so over the course of a four-week major tournament, where the quality of managers is lower than in club football on average. In this article, we look at the top five tactical switches of the tournament; unsurprisingly, winners Italy are featured as well.

Written by Ahmed Walid.

Italy played the final against England, whose earlier demons were brought back to life again, as Gareth Southgate’s questionable in-game management brought back memories of that match against Croatia in Moscow.

Unlike Southgate, Luis Enrique and Kasper Hjulmand’s in-game changes brought Spain and Denmark closer to the final, but only a penalty shoot-out against Italy and a persistent attacking approach from England stopped them.

From Roberto Martinez’s half-time switch in formation against Denmark to the Czech Republic’s right side overloads When one team has more players in a certain area or zone than the other team. against the Netherlands, here’s your top five tactical switches of the tournament.

Spain changing their approach in possession

After two draws and many missed chances, Luis Enrique tweaked Spain’s approach in possession despite creating multiple chances against Sweden and Poland. Their initial approach in the first two games was based on triangular combinations out wide between the fullback, central midfielder and wide forward with the center midfielder dropping deeper than the other two.

Then in the game against Slovakia, he switched. Bringing Pedri and Koke closer to Sergio Busquets in the middle, while keeping the full backs deeper in the buildup.

This change improved Spain’s ability to penetrate and allowed for more passing combinations between Pedri, Koke and Busquets, as the midfield trio were now much closer to each other.

It also meant that Spain were not stuck in a U-shaped circulation of the ball, When a team has possession on the sides of the pitch and with their own central defenders, this is called a ‘U-shape’, because it resembles the letter U. . they can now find Pedri or Koke in between the lines. From there, the Spanish duo can find players arriving free in the final third. The one-third of the pitch that is closest to the opposition’s goal.

Adding to that, the change in approach helped in utilizing Alvaro Morata’s link up play. Now the forward can drop to link with the midfield trio instead of just waiting inside the box for the wing play to be successful.

The most obvious example of this was the game against Italy.

Enrique strikes twice

Going into the game against Italy, Spain’s starting eleven consisted of a front three of Ferran Torres, Mikel Oyarzabal and Dani Olmo. Both Morata and Gerard Moreno were named on the bench, with Olmo centering the front three on the pitch.

As expected, Olmo dropped deeper than Morata used to. Forming a four-versus-three against Italy’s midfield. The overload presented a free accessible player behind Italy’s midfield, whether that was Olmo or Pedri.

As a result, Spain controlled the first half and their most dangerous chance in that half came from the overload in midfield. Jorginho had to cover both Olmo and Pedri, choosing to go with Olmo which meant Pedri was free to receive in between the lines. The young player of the tournament then found Oyarzabal in the box, but the latter failed to control the pass.

Italy adjusted their defensive shape in the second half by dropping Ciro Immobile on Busquets, leaving Jorginho with the sole task of marking Olmo as Nicolò Barella and Marco Verratti marked Pedri and Koke respectively.

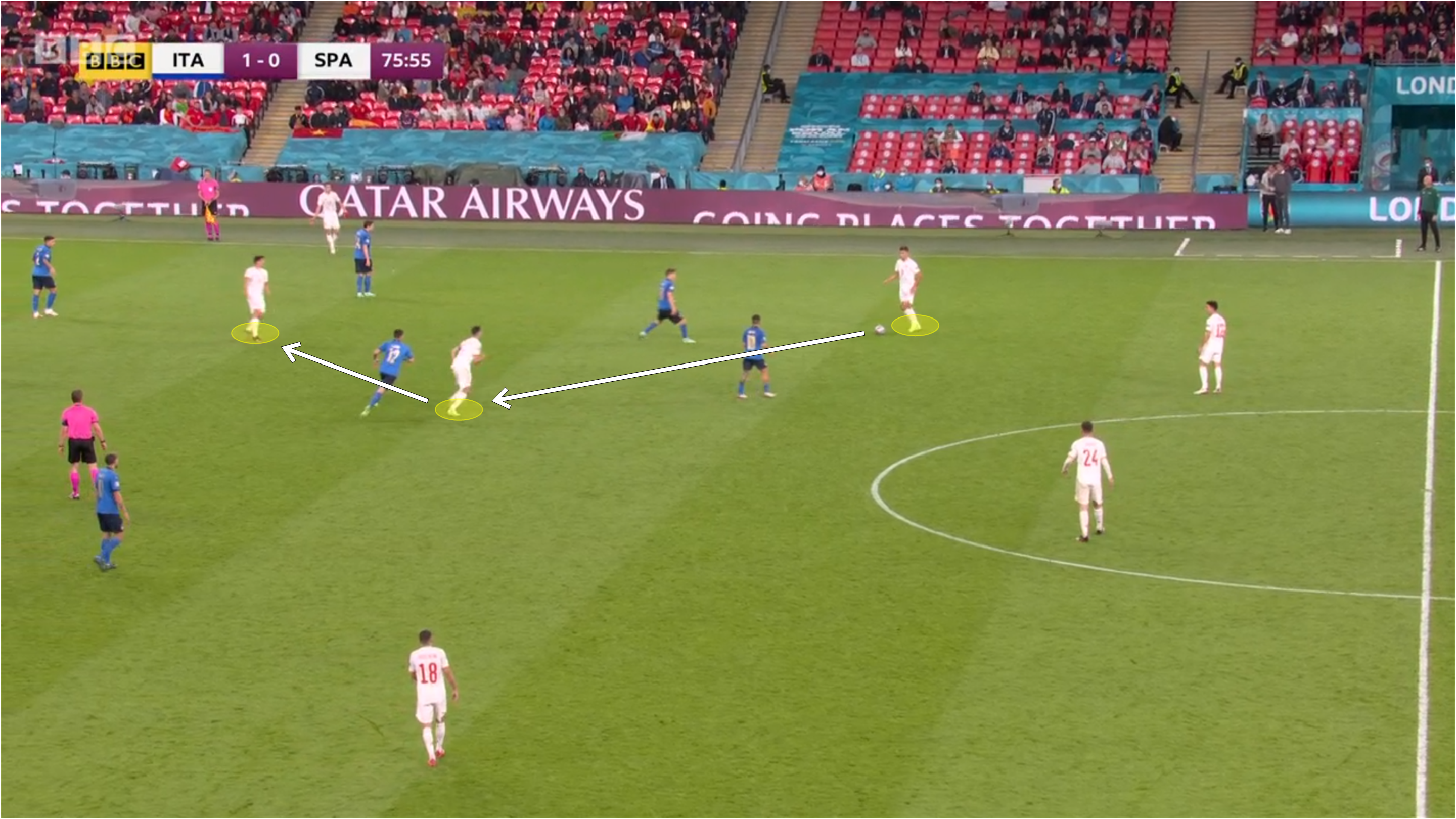

This reaction from Italy halted Spain’s threat a bit, that’s until Enrique struck again. Introducing Morata and Gerard Moreno and moving Olmo wide left while Moreno stayed wide right. Their task was to move from outside to inside behind the Italian midfield.

Spain’s equalizer combined both attacking plans, Morata dropped deep to present a passing option. Then Olmo’s movement inside allowed Morata to combine with him, putting Morata in a one-versus-one situation against Donnarumma.

Denmark’s flexibility

Denmark’s four goal demolition of Wales assumes it was an easy task in the round of 16. However, in the first 15 minutes of the game Aaron Ramsey’s presence behind Denmark’s midfield duo of Thomas Delaney and Pierre-Emile Hojbjerg, and Gareth Bale’s darts inside caused problems for the Danish side.

Wales were in control of the game until Hjulmand changed the shape from 5-2-3 to 4-3-3, moving Andreas Christensen into a holding midfield role to minimize the space either Ramsey or Bale could have in front of Denmark’s defense.

The tweak worked and Denmark regained control of the game through better buildup play as well as minimizing the space for Wales between the lines.

Attacking the danger

Prior to England’s face-off against Denmark, the looming question was whether England would play in a back three to negate the attacking prowess of Denmark’s left wing-back, Joakim Maehle, or continue with the back four as seen against Ukraine’s wing-backs.

The answer was the second option and England neutralized Maehle by constantly attacking the space behind him.

In the first half it brought England the equalizer and another chance for Raheem Sterling that Kasper Schmeichel excellently saved. Then after Jannik Vestergaard won the battle in the second half by defending the space behind Maehle, Southgate upgraded the attack by moving Sterling there.

“Bukayo (Saka) had settled into the game. He started a bit nervously, but he was playing well. But we just felt Jack (Grealish) could give us even more at that moment and Raheem running at Vestergaard on the other side, that was a change we fancied seeing as well.”

Eventually, it brought England the winner as Sterling dribbled past Maehle to win a penalty which Harry Kane missed then scored the rebound to take England to the final.

Roberto Mancini’s changes bring Italy back from the dead

45 minutes final, England were lauded for their defensive display. Restricting Italy to low quality chances and defending the channels from where Lorenzo Insigne and Barella scored against Belgium in the quarter-finals.

England were helped by Immobile’s lack of movement towards the ball. Meaning that the space between Kalvin Phillips and Declan Rice wasn’t attacked and Italy’s attacks through the channels were neutralized.

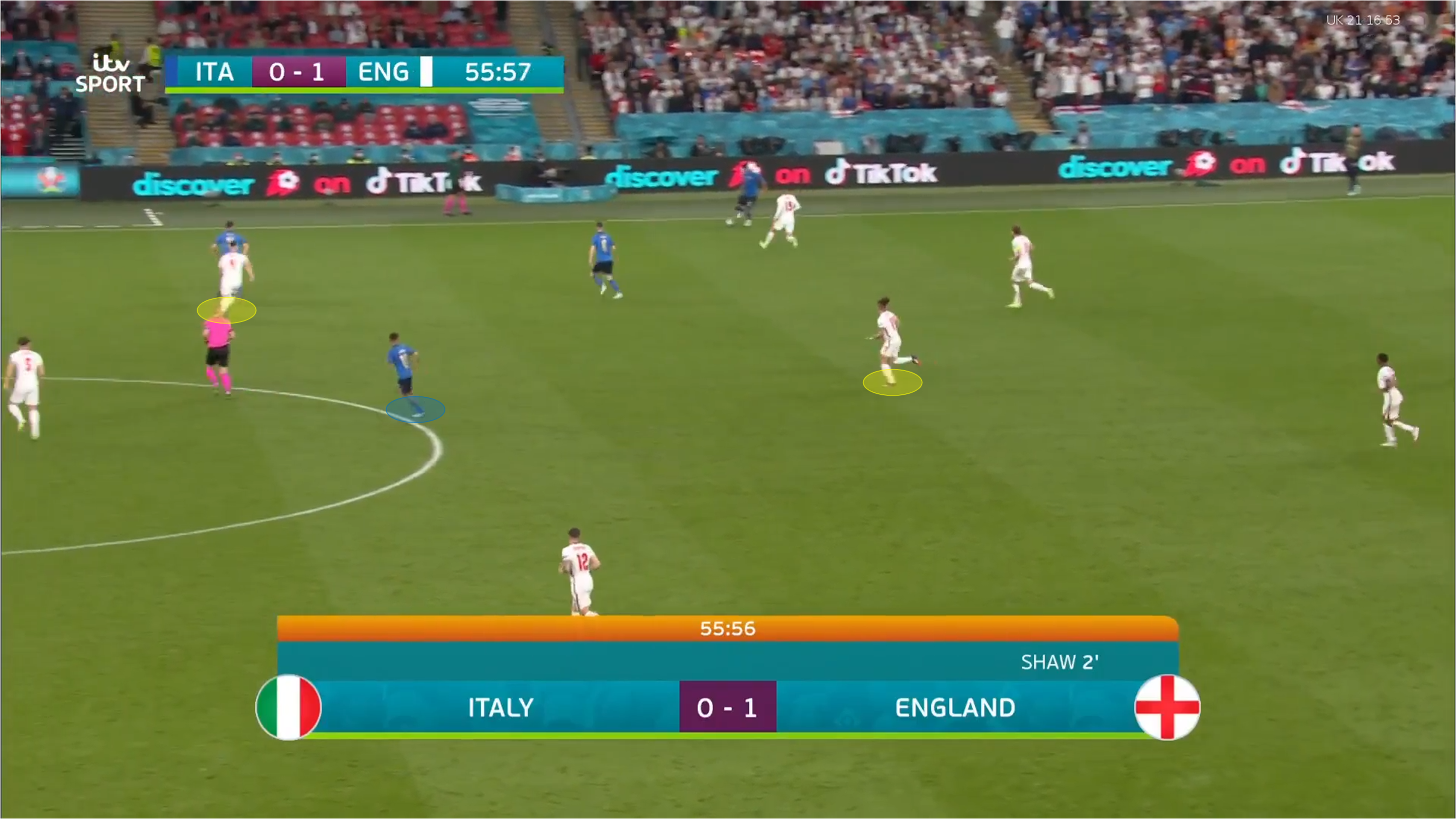

Substituting Immobile was inevitable and in the 55th minute Mancini introduced Domenico Berardi and Bryan Cristante instead of Immobile and Barella, moving Insigne into a central position. Insigne dropped and tried to link play from behind England’s midfield duo of Phillips and Rice.

That was not the only tweak though. Giorgio Chiellini pushed forward from the left side, putting Sterling in an uncomfortable position. If Sterling moved up to press Verratti, there’s a clear pass into the unmarked Chiellini. As a result, Sterling sat deep, unable to move forward to press Verratti.

As for Phillips and Rice, the constant presence of Insigne behind them prevented them from moving forward to press Verratti. The Italian midfielder had total control of the play.

Through these minimal adjustments Italy got the upper hand and constant pressure finally led to the equalizer before penalty shoot-outs saw them crowned as European champions for the second time in their history.

This article is free to read. If you want to support our work, consider taking a subscription.

Comments